Life and Community

Our lives and those of our parents and their ancestors have been affected by a combination of cultural, religious and family traditions and the larger historical events of Galicia, the region of Austria-Hungary where they lived. Our "Galitzianer" ancestors were strongly affected by the "order and modernization" that Austro-Hungarian authorities imposed on the traditional Jewish shtetls. One lasting effect of this "order" was the requirement that all citizens adopt and use family surnames, which explains the preponderance of German-language family names among Galician Jews. The Austro-Hungarian requirement to register births, marriages and deaths with the civil authorities has resulted in vital registers that survived two wars and are so important to present-day genealogists.

Our lives and those of our parents and their ancestors have been affected by a combination of cultural, religious and family traditions and the larger historical events of Galicia, the region of Austria-Hungary where they lived. Our "Galitzianer" ancestors were strongly affected by the "order and modernization" that Austro-Hungarian authorities imposed on the traditional Jewish shtetls. One lasting effect of this "order" was the requirement that all citizens adopt and use family surnames, which explains the preponderance of German-language family names among Galician Jews. The Austro-Hungarian requirement to register births, marriages and deaths with the civil authorities has resulted in vital registers that survived two wars and are so important to present-day genealogists.Our ancestors were also impacted by the need to survive and, if they could, even thrive in a primarily hostile and constantly changing environment. After World War I they found themselves living in the restored Republic of Poland whose frequently hostile relationship with its Ukrainian inhabitants further stressed Jewish life in the region. However, the most compelling and far-reaching impact on our lives came with World War II and the Holocaust.

Fortunately, many of our First Generation survivors who spent significant parts of their lives in Drohobycz, Boryslaw and the surrounding areas can still contribute their first hand experience to our understanding of life there. From them we learn about strong family ties, vibrant community life, and a widely diverse social spectrum ranging from the oil barons and the wealthy to the neediest families, from the most luxurious homes in Drohobycz to the poorest neighborhoods, from its busy city streets to the dirt roads of Boryslaw and Schodnica and the smaller Jewish communities of Urycz, Kropiwnik, Medenice, Tustanowice and others.

Thus, we can re-live the stories, images and the personal portraits that have been contributed by members of the organization to these pages and the chapter, "Remember, Never Forget".

Demographics

The 1869 census shows the number of Jews living in Drohobycz at the beginning of the oil boom to be 8,000. The establishment of the petroleum industry had stimulated a vast migration to the region so that by the end of the nineteenth century Drohobycz had burgeoned into a wealthy regional center. Economic growth had fostered the establishment of various supporting industries, commerce and services. By 1939, on the eve of World War II the Jewish population had grown to about 17,000, representing approximately one third of the city's population.

The 1869 census shows the number of Jews living in Drohobycz at the beginning of the oil boom to be 8,000. The establishment of the petroleum industry had stimulated a vast migration to the region so that by the end of the nineteenth century Drohobycz had burgeoned into a wealthy regional center. Economic growth had fostered the establishment of various supporting industries, commerce and services. By 1939, on the eve of World War II the Jewish population had grown to about 17,000, representing approximately one third of the city's population.The Jewish population in neighboring Boryslaw also grew rapidly, from approximately 1,000 in 1860 to about 13,000 in 1939, as the city developed into one of the major industrial centers in Poland. As with many boom towns, the municipal and community infrastructures of the sleepy nineteenth century village were confronted with the need to keep up with the town's accelerated growth.

Religious Life

Jewish communities of the late nineteenth century were forced to contend with growing diversity and a dynamic environment and experienced profound changes. Like other towns and villages of the time, Drohobycz and Boryslaw's traditional Jewish population was composed of Hassidim, Mitnagdim (opponents of Hassidim) and Maskilim (the Enlightened, people who belonged to the Haskala movement).

Jewish communities of the late nineteenth century were forced to contend with growing diversity and a dynamic environment and experienced profound changes. Like other towns and villages of the time, Drohobycz and Boryslaw's traditional Jewish population was composed of Hassidim, Mitnagdim (opponents of Hassidim) and Maskilim (the Enlightened, people who belonged to the Haskala movement).Drohobycz had several prominent rabbis, known as the "Drohobyczer Rebbes," and their followers. Most notable of these was the so-called Shapiro dynasty. Among the orthodox rabbis, one of the best known was Rabbi Yaakov Avigdor, who held a Ph.D. in philosophy and led his congregation until the Holocaust .

Dozens of Synagogues were scattered throughout the city, some built in magnificent architectural style. The Great Synagogue founded by the Haskala movement in the mid-nineteenth century, was among the largest and most splendid in all of Galicia. To this day, after standing in ruins for more than half a century and now being renovated, the remains of the Great Synagogue is a testament to its former grandeur.

The Jewish community of Boryslaw grew rapidly at the turn of the twentieth century due in large part to the growth and development of the petroleum industry. Its community leaders demanded independence from the tutelage of the Drohobycz kehila and at the end of 1928, Boryslaw finally became an independent community.

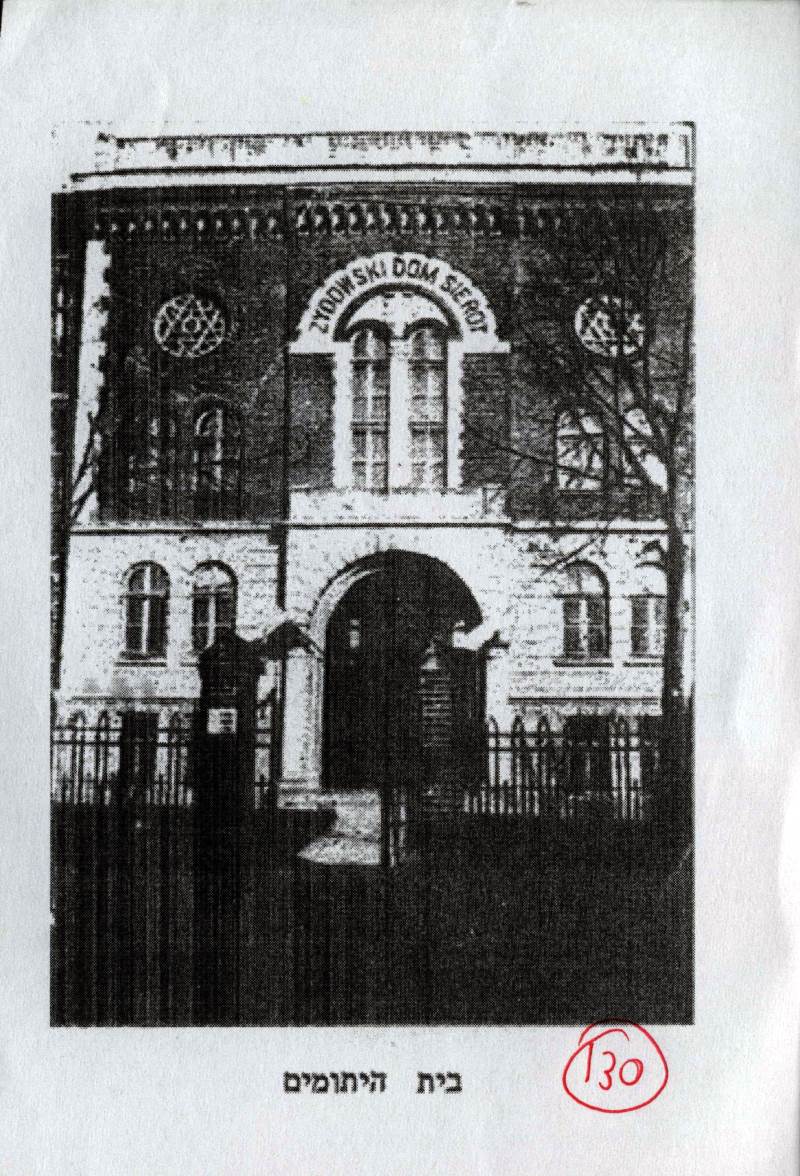

Many seminaries (Beit Midrash), Talmud Torah, "Tarbut" (culture) schools and other Jewish educational institutions in Drohobycz and Boryslaw attracted students from religious families. The opening of Beit Jacob for Girls allowed religious families to provide education to their daughters. Community welfare institutions and traditional benevolent societies (Gmilut Chesed) multiplied and were highly active, which was customary in Galician towns. The Drohobycz Orphanage was renowned in all of Galicia and was generously supported by local wealthy Jewish industrialists as well as native Drohobyczers who had emigrated abroad.

Education

With the discovery of petroleum in the region, many influential and well-to-do Jews were drawn to Drohobycz and the neighboring towns and villages of Boryslaw, Schodnica, Tustanowice, Bania Kotowska and Mraźnica and created an increased demand for quality education. The proportion of Jewish students in public schools grew and a secular Jewish private high school, sponsored by the Haskala movement, opened in Drohobycz in the mid-nineteenth century. Jewish families sent their children to school despite the relatively high tuition. A private (non-denominational) high school opened in Boryslaw as well. (See: The Story of Daniel and Natalle Hochman)

With the discovery of petroleum in the region, many influential and well-to-do Jews were drawn to Drohobycz and the neighboring towns and villages of Boryslaw, Schodnica, Tustanowice, Bania Kotowska and Mraźnica and created an increased demand for quality education. The proportion of Jewish students in public schools grew and a secular Jewish private high school, sponsored by the Haskala movement, opened in Drohobycz in the mid-nineteenth century. Jewish families sent their children to school despite the relatively high tuition. A private (non-denominational) high school opened in Boryslaw as well. (See: The Story of Daniel and Natalle Hochman) In the late 1860s, Asher Zelig Lauterbach, a wealthy industrialist and a typical Maskil, had a profound effect on the Drohobycz community through his writings and philanthropy. An outstanding and talented scholar of both traditional and secular learning, he wrote many articles in Hebrew on both industrial matters and religious commentary. He founded a Jewish hospital, a library, a reading room and a branch of Allianz in Drohobycz, and aided Jewish refugee victims fleeing pogroms in Russia. His incisive publications on the state of Jewish education in Galicia and Drohobycz had a significant impact on the city's secular education and cultural life.

The Economy and Professional Life

Boryslaw of the 1920s and 1930s was not very progressive. In his book, Exit from Hell, Mordechai Markel describes the old, small, attached homes, some with tin or even thatched roofs and lacking running water or indoor plumbing. (see: Exit From Hell- Hebrew)

Boryslaw of the 1920s and 1930s was not very progressive. In his book, Exit from Hell, Mordechai Markel describes the old, small, attached homes, some with tin or even thatched roofs and lacking running water or indoor plumbing. (see: Exit From Hell- Hebrew) However, there were also well-appointed Jewish homes. Arye (Leon) Wirzberg describes his family's large apartment in Boryslaw with indoor plumbing and central gas heating. Several other wealthy Jewish families lived in the same building and enjoyed the same comforts.

As the community attained a higher level of education came a substantial increase of high school graduates who applied for higher education in Lvov and other cities. The numbers of professionals, doctors, lawyers, engineers, economists, agronomists and others also increased in our communities.

Thousands of other Jewish families earned their living as trades' people or in the oil industry either as professionals or as laborers. Bezalel Linhard noted in his memoirs that those working in the oil industry earned a good living. (See: "I Believed I would Survive" by Bezalel Linhard- Hebrew)

Many worked in the service industries, including barbers and even Jewish taxicab drivers. Information about the transportation in those days and the important part that Jewish cab drivers played in the city's life can be found in "Exit From Hell" by Mordechai Markel (Hebrew) and in Abraham Hauptman's short story, "The Granda" by Abraham Huptman (Hebrew).

As is often the case, those with meager livelihoods found themselves without a source of income during hard times. Such was the case, for example, in 1925 when the City Council of Boryslaw closed one of the markets in which many shops and stalls were operated by Jewish families. The dismissal of Jewish workers in the oil drilling and refineries occurred intermittently since the beginning of the century and peaked that same year. Several Jewish professional associations were established, some more effective than others. During those tough times, even some high school graduates could not find employment.

In 1935, the unemployment rate soared as high as 25%. Soup kitchens were opened and in 1937, 40% of the region's Jewish residents required some type of assistance.

During these difficult times, the wealthy in Drohobycz used the educational system and networks to provide support and welfare for children and youth. Hot meals were served and clothing and educational materials were distributed to the needy on a daily basis. Boryslaw's Jewish orphanage served as a center of food distribution for the needy and their children.

During these difficult times, the wealthy in Drohobycz used the educational system and networks to provide support and welfare for children and youth. Hot meals were served and clothing and educational materials were distributed to the needy on a daily basis. Boryslaw's Jewish orphanage served as a center of food distribution for the needy and their children.Some small Jewish communities in the villages and little towns surrounded Boryslaw and Drohobycz. Itzhak Hal-Or/Heller in his short essay tells us about his very small village of Medenice (See: "My Little Town Medenice" by Itzhak Hal-Or/ Heller- Hebrew), where most of the Jewish population were merchants, craftsmen and some farmers.

Zionist Activity

The growing strength of the Jewish population raised the bar for education and increased the desire to study.In My Yesterday, David Horowitz describes the Zionist movement composed of educated young people, rooted in tradition, and familiar with the western culture, many of whom dreamt of a Zionist revival and also of poorer youth who could not see a future for themselves in the Diaspora.

Much like other towns throughout Galicia, Drohobycz, Boryslaw and even Schodnica embraced the Zionist movement. Zionist youth organizations flourished. Most of them had branches in Drohobycz and agricultural training farms operated in Boryslaw and in Schodnica.

According to Abraham Hauptman the Polish authorities did everything in their power to encourage Zionist movements, hoping to get rid of the Jews (See: "Beautiful Years, Barefoot Years" by Avraham Hauptman-Hebrew).

Many political parties and organizations existed in Drohobycz and Boryslaw in spite of the relatively small size of these towns. The Jewish communities flourished with Zionists, socialists, German and Polish-speaking intellectuals, and ultra-Orthodox and Hebrew scholars.

Many political parties and organizations existed in Drohobycz and Boryslaw in spite of the relatively small size of these towns. The Jewish communities flourished with Zionists, socialists, German and Polish-speaking intellectuals, and ultra-Orthodox and Hebrew scholars.Eventually a single common Youth Center was established. The groups engaged in social activities and in learning Hebrew, Zionist ideals, the history and geography of Israel, and songs. For Jewish youth who did not have the opportunity for secondary education, these Zionist organizations and their activities constituted their continuing education.

Cultural Life and Clubs

Our own people, who lived there at the time, are the best source to tell us about the everyday life in Drohobycz and Boryslaw. They describe a heterogeneous community comprised of modern/traditional and secular groups, a very diverse social life, clubs, sports, theater ("Repertory Theatre of Drohobycz ") and cinema. Despite the fact that Jews were a minority in the general population, they set the tone in matters of education and culture. Several sports associations were extremely active. The boys of Boryslaw, sometimes called "angels" (Malach's), started the "Kadima" sports club. Hockey, tennis, volleyball teams were very active in Drohobycz.

Our own people, who lived there at the time, are the best source to tell us about the everyday life in Drohobycz and Boryslaw. They describe a heterogeneous community comprised of modern/traditional and secular groups, a very diverse social life, clubs, sports, theater ("Repertory Theatre of Drohobycz ") and cinema. Despite the fact that Jews were a minority in the general population, they set the tone in matters of education and culture. Several sports associations were extremely active. The boys of Boryslaw, sometimes called "angels" (Malach's), started the "Kadima" sports club. Hockey, tennis, volleyball teams were very active in Drohobycz.Many of our people describe a vibrant and pleasurable lifestyle. Shevach Weiss and others talk about social and family picnics, summer holidays in the village and youth camps in the forests (See: Shevah Weiss-Hebrew). Zev Mayer recalls children ice skating in winter and spring, picking wild raspberries in the woods and summers spent out of town in the villages of Rybnik and Zauminka. Zvi Rotenberg remembers the cultural activities mainly revolving around the Jewish holidays and focusing on children and youth.

The "Jewish Home" in Drohobycz was a center of varied cultural activities including drama and Jewish theater groups, lectures, Hebrew study, orchestra and choir.

Jews comprised only several hundred of Schodnica's total population of 3,000. Yet the Jews led a vibrant cultural and social life that included a library, theater and a movie theater. In his short story about the youth movements Abraham Hauptman proclaims that it was a social "must" to see the Schodnica productions (See: "Beautiful Years, Barefoot Years" by Avraham Hauptman - Hebrew).

Bibliography:

Extensive Description of Life and CommunityYizkor Book for Drohobycz, Boryslaw and Vicinity

History of the Jews of Boryslaw

Boryslaw - Geography

Boryslaw of our Youth

Grandma's Recipe Book

Religious Life in Drohobycz

The Religious Life of the Jews of Drohobycz

The Historical Efforts to save the ancient synagogue in Drohobycz:

My Memories of Drohobycz

Religious and Cultural Life in Boryslaw

History of the Jews of Boryslaw

Boryslaw of our youth

The Schodnica Community

I Sang for You Schodnica / Abraham Hauptman (Hebrew)

Eulogy (Hebrew)

Schodnica / Joseph Kitai (Hebrew)

Our Own Nicknames / Abraham Hauptman

Local Newspapers

Glos Drohobycko-Boryslaw-Samborsko-Stryjski

Villages in the Drohobycz area

Updated list of villages in Drohobycz region

Additional Reading

Sights and Images from Drohobycz, Boryslaw and Environs

David Horowitz, My Yesterday ( Hebrew), 1970

S. Shalom; Drohobycz Memoirs ( Hebrew)

Henryk Grynberg, Drohobycz, Drohobycz and Other Stories, Penguin Books, 2002