Black Gold!

A question to ponder: what would have been the fate of Boryslaw, Drohobycz and the surrounding villages were it not for the discovery of oil in the area in the nineteenth century?

A question to ponder: what would have been the fate of Boryslaw, Drohobycz and the surrounding villages were it not for the discovery of oil in the area in the nineteenth century?

There is truly no clear cut answer. Boryslaw may have remained a small sleepy town in the shadow of the larger district city of Drohobycz. Perhaps their fate and the fate of the towns in the vicinity would have been the same as that of the other Jewish shtetls in Galicia, a slow but steady decline beginning in the late nineteenth century that accelerated after World War I.

A Beautiful Yellow

Years before it was known as mineral wax or earth wax – the locals used to dig out rocks with beautiful yellow Ozokerite veins. These veins were cleansed using primitive methods and the material was used in candle making and later as a means to insulate moisture for boats and ships.

Years before it was known as mineral wax or earth wax – the locals used to dig out rocks with beautiful yellow Ozokerite veins. These veins were cleansed using primitive methods and the material was used in candle making and later as a means to insulate moisture for boats and ships.

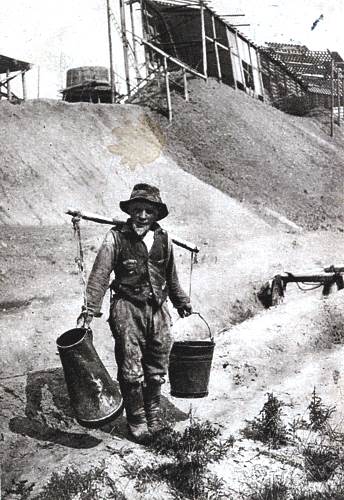

The wax excavations were called GRUPA at the time and were serially numbered and registered. The rocks and soil extracted from the primitive ozokerite mines were deposited in what formed large hills known in Polish as Wysypy. This landscape of mud hills dominated Boryslaw and gave the town an apocalyptic look, as evidenced in period post cards and personal accounts. The community poor, so called Lepaks, would collect rock debris to extract whatever was left over to make a meager living.

Smelly Mud

For years the peasants in the Drohobycz district collected crude oil in wooden buckets to sell in the town market. They used the thick oil called ROPA as a lubricant for wagon wheels and as a healing agent for skin ailments. The crude oil was a sticky dark liquid that gave off a foul odor smoke when burned. Around 1810, Joseph Hecker, a Jewish geologist and salt mine inspector from Prague working in the nearby town of Truskawiec was prospecting for oil and endeavored to separate the flammable material from the mud. He was successful and discovered that the liquid residue burned easily. He used it in lamps to illuminate buildings in the towns in the Drohobycz area, and with a colleague, established a small petroleum distillery. By 1817 they signed a contract with the town council of Prague for the delivery of distilled petrol to light the city's streets. Due to the poor road conditions in Galicia, delivery was unreliable, the business failed and Hecker's initiative fizzled.

For years the peasants in the Drohobycz district collected crude oil in wooden buckets to sell in the town market. They used the thick oil called ROPA as a lubricant for wagon wheels and as a healing agent for skin ailments. The crude oil was a sticky dark liquid that gave off a foul odor smoke when burned. Around 1810, Joseph Hecker, a Jewish geologist and salt mine inspector from Prague working in the nearby town of Truskawiec was prospecting for oil and endeavored to separate the flammable material from the mud. He was successful and discovered that the liquid residue burned easily. He used it in lamps to illuminate buildings in the towns in the Drohobycz area, and with a colleague, established a small petroleum distillery. By 1817 they signed a contract with the town council of Prague for the delivery of distilled petrol to light the city's streets. Due to the poor road conditions in Galicia, delivery was unreliable, the business failed and Hecker's initiative fizzled.

The actual "Eureka moment" occurred years later. In the 1840s, Abraham Schreiner, a small landholder in the Wolanka area who had experience in Ozokerite candle making, began experimenting with the distillation of crude oil that he found on his land. Like others in the area, Schreiner discovered that his land yielded few crops. During the spring melt and after heavy rainfalls, smelly, oily mud would seep out of the ground. Clothes would get stained and no amount of scrubbing would remove these stains. It occurred to Schreiner that by separating the oily liquid from the mud, he would be able to obtain a clean burning material. After experimenting with inferior equipment to reduce the smoke and improve incineration, and after sustaining severe burns, Abraham Schreiner brought the dark liquid he distilled from crude oil to Ignacy Łukasiewicz, a pharmacist from Lwow. In 1853 Łukasiewicz was able to purify Schreiner's distillate into pure oil, which they called NAPHTA. By 1855 the hospital in Lwow was lit with oil lamps and in 1858 the Emperor placed a direct order for oil to light Vienna's North Train Station.

The discovery of this "black gold" attracted hundreds of speculators and fortune seekers. With no pre-existing order in place, people staked their claims by grabbing whatever land they could, erecting tents and huts and digging. In most cases they were able to come-up with wax, oil or both, depending on the piece of land they occupied and dumb luck. Soon, Boryslaw, Truskawiec and the surrounding villages were filled with holes and piles of mud.

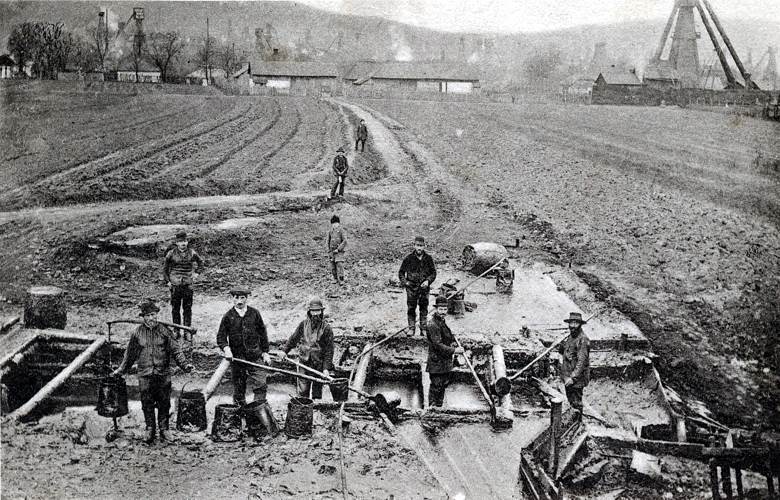

The oil diggers, or as they were called "The Klondike People," dug deeper and wider in order to lower a ladder and then themselves into the pits to access more of the black gold. Those who could afford it hired Boykos – poor Ruthenian Ukrainians villagers for the most difficult and dirtiest jobs. This was a period of relatively good relations between the Jewish population and their Ukrainian neighbors.

In the frenzy some prospered while others lost everything. The chaotic working conditions were appalling with derricks and trenches collapsing, toxic methane gas seeping from the primitive excavations and a constant threat of fire, which broke out and spread out of control frequently.

The Black Gold Age

Vision, the instinct for adventure and the dire need for sources of livelihood propelled Drohobycz, Boryslaw and the area into an economic miracle dubbed the "California of Galicia". The first oil wells opened in 1893 – 1894. At the beginning of this burgeoning industry, Jews held most of the positions – day and skilled laborers as well as various levels of management roles. And there were the Jewish oil magnets – those who owned the oil wells, the refineries and the marketing channels (see "The Jewish Oil Barons"- Hebrew)

Vision, the instinct for adventure and the dire need for sources of livelihood propelled Drohobycz, Boryslaw and the area into an economic miracle dubbed the "California of Galicia". The first oil wells opened in 1893 – 1894. At the beginning of this burgeoning industry, Jews held most of the positions – day and skilled laborers as well as various levels of management roles. And there were the Jewish oil magnets – those who owned the oil wells, the refineries and the marketing channels (see "The Jewish Oil Barons"- Hebrew)

By the end of the 19th century about 3000 Jews were employed in the oil industry. Boryslaw became the undisputed oil capital of Galicia. In addition to oil, this area also was rich in natural gas. Jews who worked menial, grueling jobs were a commonplace in Boryslaw - a phenomenon not seen anywhere in Galicia. Also of note are those, who through entrepreneurship, ingenuity and originality developed and improved operations and marketing methods, which turned the crude oil wells into an industry. At that time most of the oil wells and most of the labor force were in Jewish hands. Even the revenues from the oil industry received a juicy nickname "Achtel" (1/8 in Yiddish) (see: About Oil Driling-Hebrew) which became the standard measurement of royalties to oil well owners.

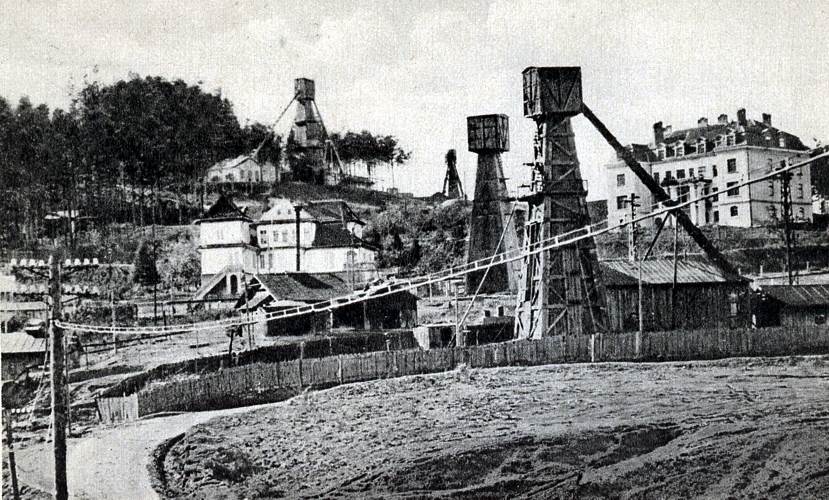

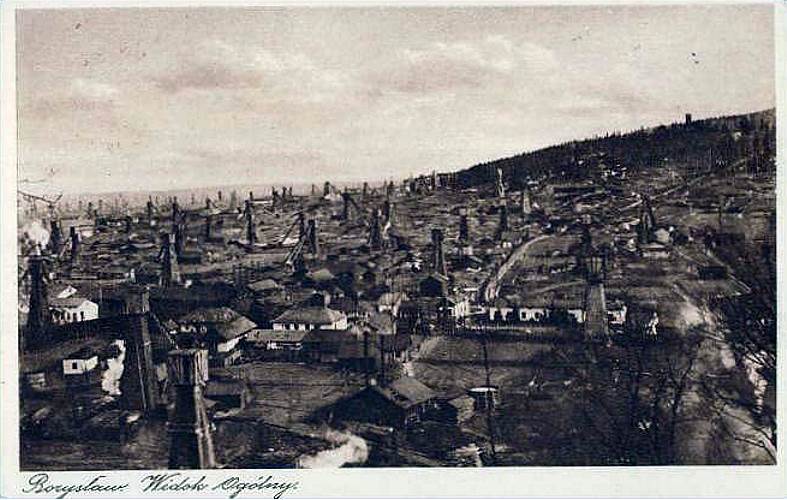

Boryslaw's landscape consisted of a maze of great mounds of dirt, pits, huts, scaffolding for lowering people into the pits and hundreds of derricks and refinery chimneys. Choking smoke, explosions of gas jets, fires and an occasional heavy stench engulfed the entire area. At night however, the town took on a "new look". Boryslaw appeared as a metropolis illuminated by thousands of sparkling lights from the oil derricks. Vacationers from Truskawiec who came to the area for the hot springs could go on nocturnal "light tours" to view the wonders.

People, horses and carts treaded the muddy oil slicked streets of Boryslaw. A 1938 tour brochure for the area describes Boryslaw as a city full of extreme contrasts – primitive derricks next to modern buildings, simple poor stalls near elegant shops.

In his memoirs Bezalel Linhard (See: "I Belived I Will Stay Alive" by Bezalel Linhard-Hebrew) describes the chaos and the environmental hazards ("but who paid attention") of strong sulfur and natural gas odors as well as the constant danger of fires due to leaky pipes that were placed under wooden sidewalks.

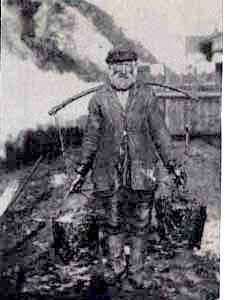

The excess crude oil from the wells and the oil seeping from the frequently cracked pipes would spill over into the ditches, streams and tributaries. A unique cottage oil industry developed in Boryslaw. Poor elderly men called Lebaks (or Lebacy in Polish) would scoop this excess oil into pails. They developed a primitive, but effective, method of separating the precious liquid from the mud by using long broom-like tools which absorbed only the oil. The liquid was then sold to the small refineries or directly in the markets for heating. There were a few who developed a primitive "production line". Yet others combined the oil excesses with sawdust into balls and sold these as torches to start fires in home stoves. Thus, with much hardship, they earned a living. Very few did well in this line of work and even fewer made a small fortune.

Amid the chaos, Jews continued to industrialize and improve oil production processes. Research and development centers were opened to improve by-product and the refinery methods. The development of an industry for equipment used in the oil industry, such as iron pipes to transfer oil to the refineries, was an ancillary outcome of Boryslaw's oil boom.

The Jewish population of Boryslaw was also involved in the production of natural gas and in constructing the pipeline networks for its conveyance. Jewish engineers were instrumental in improving gas measurement and enhancing gas production methods. Finance and marketing networks were developed, facilitating the expansion of distribution to the entire European continent.

Oil was also discovered in the neighboring towns of Schodnica, Kropiwnik, Tustanowice and Mraźnica, and the industry grew and expanded there as well.

Medicinal and healing properties were attributed to the sulfur-rich hot springs (Naftusia) in neighboring Truskawiec which became a resort town attracting vacationers from all over Europe.

Drohobycz flourished. It was the only town in Galicia attracting international finance and interests. As befitting a district capital, the refineries, marketing, trade and finance were centered in Drohobycz. Jews who profited from the oil and the related financial and legal services built magnificent homes, improved the education system and established a modern hospital.

Some of the oil companies under Jewish ownership grew and became significant at the beginning of the modern oil industry. Polmin, Nafta, Bakenrot, Galicia and Gartner were just a few of the enterprises launched and operated by Jewish entrepreneurs. The lucrative industry and the increase in global demand for oil at the turn of the century attracted Austrian banks and international oil companies from Germany, England and Belgium. Luxurious buildings were established to house the regional headquarters of these international companies and the city's infrastructure was improved.Hard Times

Also around the turn of the century, the Austro-Hungarian authorities started regulating the unruly industry. Regulation and the vested interests of the multinational companies exposed the companies under Jewish ownership to stiff competition and a frequently hostile environment. Many Jewish companies were sold, closed or forced to cut back operations. The foreign companies refused to hire Jews, leading again to high unemployment among Boryslaw's Jewish population. During this period, with the assistance from Agudat Zion, Alliance Israélite Universelle (Kol Israel Haverim) and the Baron de Hirsch Fund, dozens of families emigrated to Israel and several hundreds to the United States and Argentina.

Oil production reached its peak before and immediately after World War I. In the 1920s the oil resources began to dwindle and the Jewish population had to find alternative sources of income. At the time that many other Jewish towns in Galicia started to decay, the "black gold age" left Drohobycz and Boryslaw with well developed infrastructure, schools and a Jewish population more educated and economically established than ever before.

Could this boom change the fate of the Drohobycz, Boryslaw and the neighboring areas Jews during the Holocaust? Apparently not. Yet when the Germans invaded Drohobycz and Boryslaw in 1941, they recognized the importance of the oil industry and continued to operate the wells and refineries. Drohobycz and Boryslaw were not bombarded by the approaching German army, the way many other polish towns were. Among the tens of thousands who were persecuted and murdered in our communities, there were several hundred Jews, who were granted the status of "essential defense industry workers of the Third Reich". Some, were lucky to survive. Dr. Berthold Beitz, a young German engineer and the manager of the oil industry under the Nazi regime managed to save the lives of many Jews under his command. In 1973, Yad Vashem recognized Berthold Beitz as "Righteous Among the Nations".

For a few of the wealthier Jews money might have helped in bribing, paying for food, or securing an escape or hiding place. However the cold chilling numbers cannot be disputed. In 1939, 32,000 Jews called Drohobycz, Boryslaw and environs their home. After the Holocaust only 400 survived..

Sources

About the oil industry in the Drohobycz area

History of the Jews of Boryslaw

Boryslaw - Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Poland - Valume II

The Oil Companies of the Drohobycz Administrative District

Schwarzes Gold und Gelber Stern

About the Jewish Oil Magnets

J. Hirschaut, Di yiddishe naftmagnatn, Coleccion El judaism polaco, Volume 101, Editor: Mark Turkow, Central Organization of Polish Jews in Argentina, Buenos Aires, 1954

Chapters from the Book "The Jewish Oil Magnets" (Hebrew)

About the Lebaks

Swiat Lebakow, Dr. A. Zyga, Nowiny I Kurier1991

About the Historical Research of Galician Petroleum

Kresowe Trojmiasto: Truskawiec--Drohobycz--Boryslaw by Stanisaw Sawomir Nicieja, 2009